- Home

- Health Initiatives

- Washington Rural Palliative Care Initiative

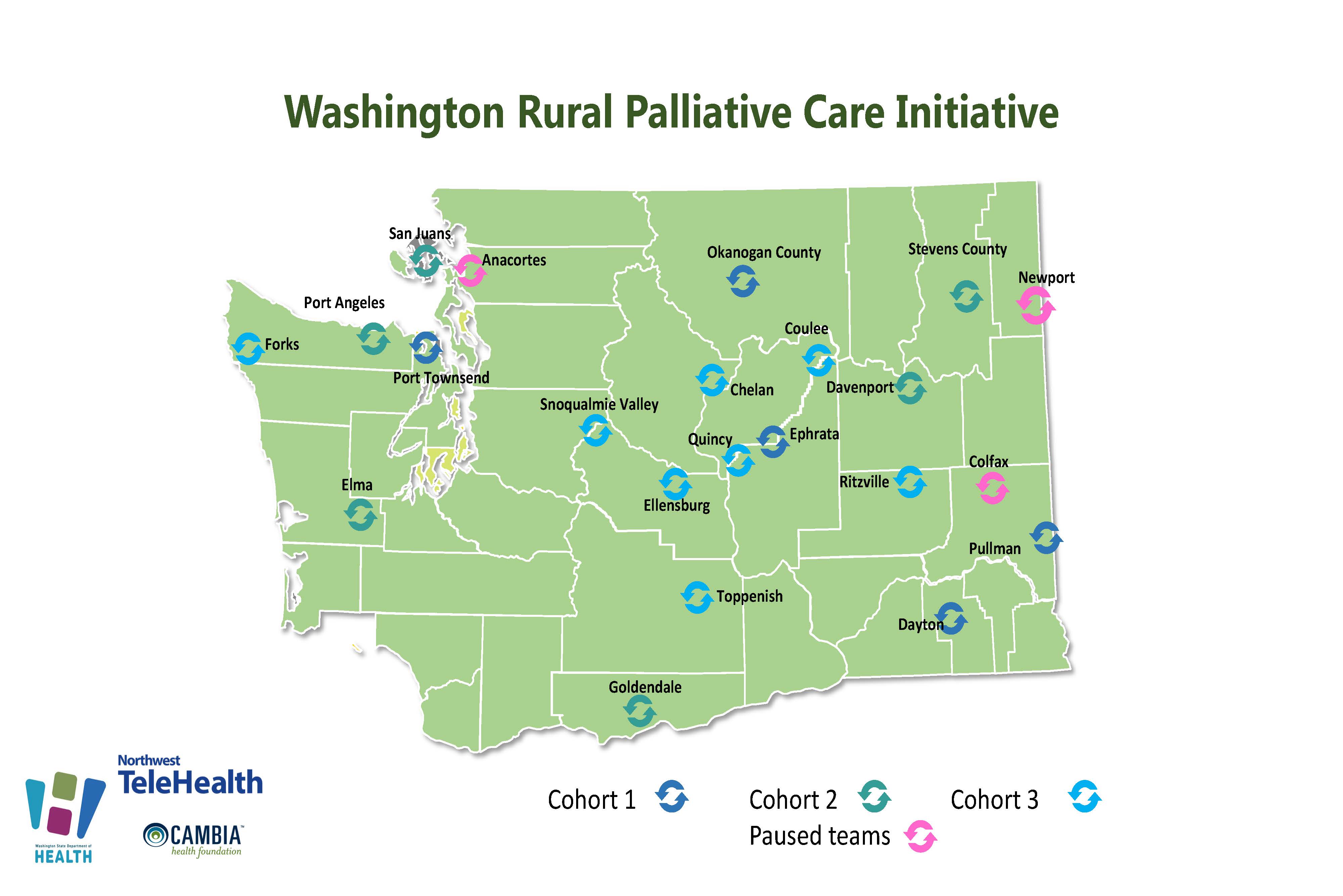

Washington Rural Palliative Care Initiative

The Washington Rural Palliative Care Initiative (WRPCI) is an effort to better serve patients with serious illness in rural communities. This public-private partnership is led by the Washington State Office of Rural Health at the state Department of Health involving over 24 organizations.

This work aims to assist rural health systems and communities to integrate palliative care in multiple settings, such as emergency department, inpatient, skilled rehabilitation, home health, hospice, primary care, and long-term care.

News & Resources

- News and Updates

-

- New Pediatric Palliative Care portal page has been added.

- Featured Resources

-

- Expanding Rural Access Through Primary Palliative Care Training: Alebra Schol, MD is a guest blogger for the Shirley Hayes Institute for Palliative Care at California State University. This brief blog discusses the inequities in access in rural and also refers the reader to the course offered by the institute called Primary Palliative Care Skills for Every Provider.

- Webinar & Podcasts

-

- Addressing Public Misperceptions About Palliative Care

- Evidence-based Practices for Changing Public Perceptions about Palliative Care

- Case Studies: Applying the Research to Change Public Perceptions about Palliative Care

- From Suffering to Wellbeing

- What is Palliative Care and How Does it Relate to NET?

- Telehealth: Dairy Cow Scheduled Complicate Things

- PC Team Resources

-

- New PC Teams Overview: This simple one-page document communicates with the WA Rural Palliative Care Initiative offers participants, and what they are asked to contribute.

- Getting started: How to create an account on this site and join a team.

What is Palliative Care?

Palliative care is specialized care for people living with serious illness. Care is focused on relief from the symptoms and stress of the illness and treatment—whatever the diagnosis. The goal is to improve and sustain quality of life for the patient, loved ones and other care companions. It is appropriate at any age and at any stage in a serious illness and can be provided along with active treatment. Palliative care facilitates patient autonomy, access to information, and choice. The palliative care team helps patients and families understand the nature of their illness, and make timely, informed decisions about care. Learn more about WA Rural Palliative Care Initiative

The Palliative Care Road Map is a FREE publication to help patients, and the people they love sort through the experience of serious illness and conditions. Healthcare teams may find it a useful tool for assisting their patients. Each section offers empathy and information to help make sense of how serious illnesses and conditions unfold over time, with listed resources and key terms defined.

To order printed copies: The Palliative Care Roadmap may also be ordered as a published booklet by logging in at MarketDirect Storefront (myprintdesk.net) or creating a MyPrintDesk account and searching for the title.

The Washington Rural Palliative Care Initiative Handbook is a publication designed to help rural health communities and organizations learn more about the framework of this initiative. Please explore the Washington Rural Palliative Care Initiative Handbook to learn more about the framework of this initiative.

Contact

Washington State Department of Health

Mandy Latchaw

Director, Washington Rural Palliative Care Initiative